“I said three years ago to the leaders in this agency, that we had 57 people at that point in time that could walk out the door for retirement. “I said three years ago to the leaders in this agency, that we had 57 people at that point in time that could walk out the door for retirement,” said Lauren Henderson, the interim director of the Oregon Department of Agriculture. For one thing, the earnest young people, like Farrar, who signed up for careers at the agency in the ‘70s and ‘80s are now retirement age. But Oregon’s Noxious Weed Program has also faced challenges in recent years. “Within the next couple of years, we had enough (bugs) for basically everybody in the state that wanted any,” he said.

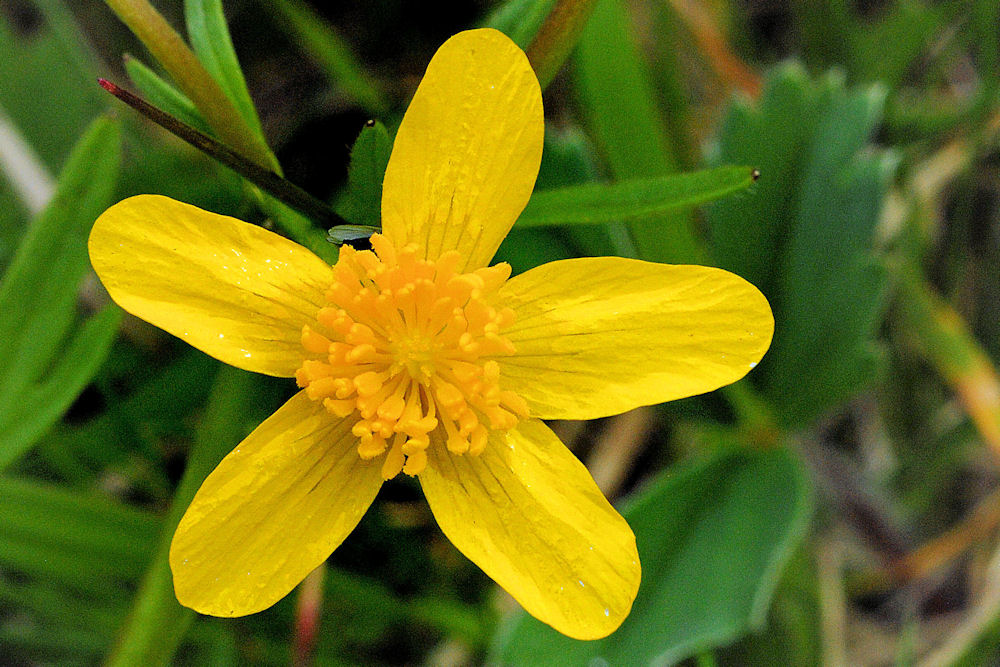

He thinks keeping the site secret, just for a while, was a good idea. That day in September, Farrar looked up 30 Mile Canyon into a sea of native sage bunchgrass and larkspur. Now, Farrar says when toadflax booms - as it does now and then - there’s a subsequent boom in the Mecinus bug population, which naturally brings the toadflax back under control. The bugs gobbled up most of the toadflax along both rivers and left native species alone. The other site, along the John Day River, he kept to himself.Īnd it worked. He decided to only tell the state about one bug placement site - along 30 Mile Canyon. Mecinus Janthinus bugs were introduced to tackle Toadflax blooms. “It was disappointing that as soon as we got established, we had sellers come in and take some,” Farrar said. Trouble was, sprinkling $500 bugs out in the open and then informing the state of their whereabouts, pretty much guaranteed the pricey critters would get poached. Still, with a $50,000 grant from the Oregon Department of Agriculture, Farrar bought 100 bugs from a supplier in Idaho. “They were new and there was nobody that really had them,” he said. The bug is called Mecinus Janthinus and it drills into the stem of toadflax - and only toadflax - to lay eggs for its larvae.īut there was a problem. Then back in the 2000s, he found a technical journal that suggested killing it with a bug from Europe. Mecinus bugs drill into Dalmatian Toadflax to lay their eggs. “We were never going to get this,” Farrar said. So the toadflax just settled in along the waterways and sent out untold millions of seeds every season. The herbicides worked well enough, but environmental laws meant they couldn’t spray within 50 feet of a stream. Over time, however, herbicides became more focused and Farrar remembers spending $100,000 to hire a helicopter for a week to spray Gilliam County’s steep canyons. The trouble was, they were crude and killed all manner of plants, not just toadflax. After World War II, herbicides came into widespread use.

But that’s exhausting and relatively ineffective.

Farmers started just pulling it out by the roots. It’s thought to have come from Europe in the ballast of ships. And neither were we.”ĭalmatian Toadflax was first noticed in Oregon in the early 1900s. And they weren’t really keeping up with it. Farmers were using more harsher chemicals to try to control it. “Toadflax had been here for years,” he said, leaning over his pickup in Condon on a dry September day, “It was just gradually taking over everything and getting worse and worse and worse. To give a sense of the scope of his department’s work, he explained what it took to control just one of the 130 weeds on Oregon’s list of noxious plants.ĭon Farrar uses a bug catcher to catch bugs so they can be taken and placed on weeds elsewhere. The lifelong rancher just retired as head of Gilliam County’s noxious weed program. To save its dying livestock, Oregon created a new Noxious Weed ProgramĮver since, people like Don Farrar, 66, have spent their careers finding and rooting out noxious weeds. When cattle and horses ate enough, alkaloids in the ragwort cause liver damage and death. If those weeds were left to their own devices, losses would mount to $1.8 billion, according to the Oregon Department of Agriculture.īack in the 1970s and 1980s, Oregon’s farmlands were hit by a nasty new weed called tansy ragwort. They choke out native species and don’t make good food for animals. While cannabis sales bring in money for the state’s coffers, invasive weeds like Toadflax, Medusa head and Cheatgrass cost Oregon more than $80 million a year. Managing weed growth in Oregon is like painting the Golden Gate Bridge in California - it’s a job that never ends.Īnd no - not that kind of weed.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)